Tagged: Mad Men

Mad Men 7×14: Those Left Behind

Dick Whitman started running away from his life long before he was Don Draper. He enlisted to escape what he was born into, and when he was given the opportunity to cut his ties he took it. He chose not to look backwards, as though the people who were part of Dick Whitman’s life ceased to exist when Dick Whitman became Don Draper.

But they didn’t. The people Don leaves behind, from Adam Whitman to Peggy Olson, go on whether or not Don is there. He can’t see himself as anything but the central character in his own life story, but Peggy and Joan, Pete and Roger, Sally and Betty…these supporting characters, in both Mad Men and Don Draper’s life, have been living their own stories all this time, and in thinking about the finale I’m far more interested in where they all end up than in whether or not Don went back to New York to buy the world a Coke. (But he totally did.)

Joan Holloway Harris

Richard tells Joan that her life is “undeveloped property” with an eye to build on it himself. He presents her with a handful of possibilities for her future that all include him. But Joan doesn’t start building until the second Ken hands her the specs for producing his technical film. You can actually see the idea come to her, that producing is something she can do herself. She’s got that rolodex, she already knows everyone.

Joan didn’t start out with heaps of professional ambition, but her transition from the office manager with an eye towards marrying out to a business woman and mother who prioritizes her career over her love life has been a natural one. Men have been nothing but disappointments to Joan, from Roger, who could give up everything for a 21-year-old secretary but not for her, to her ex-husband, the rapist, to Bob Benson, who looked at marriage as a business arrangement, to Richard, who didn’t like making plans unless they were his own. And that’s not to mention the partners at Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce, who sold her body for a fancy client, or the men at McCann who wouldn’t take her seriously. Joan’s desire to put her name on the door, to run her own show, makes perfect sense. It’s worth so much more to her than a ring or a nice vacation. She finds peace in her work.

In naming her production company Holloway Harris (because “you need two names to make it sound real”), Joan is nodding to both the woman she was and the woman she’s become. In her bustling living room office, reminiscent of the early days of SCDP, she doesn’t have to answer to anyone but herself.

Peggy Olson

As fun as it is to think about Peggy and Joan teaming up, their names next to each other on some office wall, they’ve never wanted the same things out of the world. Peggy’s life is not undeveloped property, she’s been building it up since the day we met her, and she thinks she knows exactly what it’s going to look like.

When Don asked Peggy what she saw in her future a few episodes back, in “The Forecast,” she told him easily: big clients, the first female creative director at Sterling Cooper and Partners, a catch-phrase to call her own. She wants fame and she isn’t ashamed of it or afraid of it. And she knows it will take time (Pete tells her she’ll be a creative director by 1980 and she comments that it seems a long way off, but we know she’s already half-way there. These past 10 years have flown by), but it’s worth the long hours, worth staring at the four walls of her office, for the pay-off.

What Peggy has not thought about is what she wants from her personal life. We’ve seen what she’s given up in that arena, from the baby she put up for adoption at the end of season 1 to a series of ill-advised affairs, to a few nice if not-quite-right men like Abe, or Stevie from the mid-season premiere. The scene where Stan tells Peggy that he loves her is all the lovelier for how it takes her by surprise, and not just surprise at his love for her but at her own love for him. As she talks herself through her feelings on the phone (always the phone with these two!) we see her dreams for the future expanding, rather than changing. She’s not sacrificing one thing to pursue another, but letting her world open up a little, for the person that knows her best.

Pete Campbell

Pete only appears very briefly in “Person to Person,” for a small scene with Peggy and then in the montage at the end, getting into an airplane with his wife and his daughter, heading off to re-start their life together in Wichita. His real farewell was in last week’s episode.

The scene between Pete and Peggy is a sweet one. Watching their professional alliance form over the last few years has been fascinating, especially as it happened in the wake of Pete’s discovery that Peggy gave up their child. She jokes, in the scene, about Harry’s revisionist history, suggesting that the three of them had some deep bond that warrants a farewell lunch even though they’ve never had lunch together before, but Peggy and Pete really did have a special relationship; even a few weeks ago he was warning her about the merger with McCann, making sure she would be alright.

Pete’s ending is a happier one than Don’s. Sure, he’s leaving New York for Wichita, but he gets his family back, he gets a real fresh start. It’s entirely possible that he’ll waste it, that he’ll go back to mistreating them the way he did the first time, but that’s not for us to know. Mad Men leaves his story here, hopeful. It gives him the capacity to change.

Roger Sterling

And Roger changes, too. Or at least he mellows. He’s always happiest when a woman is bossing him around, even as he complains about it, and whether Caroline is forcing him to fire Meredith (who takes it better than perhaps anyone ever has), or Marie is kicking him out of bed for trying to make demands of her, Roger seems more content than we’ve seen him since his LSD days.

He’s also taking some real responsibility for Kevin for the first time, owning up to him financially if not officially, even taking him out for an afternoon. This is more than just sending Joan Valentine’s flowers in Kevin’s name, though it’s still far from actual parenting. The scene between Roger and Joan is a sweet one, real closure on one of the strongest relationships the show produced.

Betty Draper

I almost wish we hadn’t seen Betty this week, as the conversation between her and Don in “Lost Horizon,” and her final moments in “The Milk and Honey Route,” gave lovely closure to a polarizing character. “The Milk and Honey Route” in particular would have been a very strong goodbye that still did justice to how difficult Betty could be, how unyielding. But here she was again in “Person to Person,” still trying to enforce her will on a future she won’t live to see.

Betty tells Don that she doesn’t want him to come home, that she doesn’t want him to take the kids, because having Don around would clue them in that something is going on. It would be too different from the status quo. But she doesn’t take into account the fact that her illness is visible, that her fights with Henry were loud. Bobby knows what’s happening, even Gene must have some idea. Betty decided not to fight her cancer, and sent Sally back to school, because she didn’t want her children to watch her die, but that will happen anyway. She isn’t going to just slip out of the world now that she’s decided to forego treatment. Six months can last a long time.

And maybe that’s the biggest argument in favor of this final appearance. Betty’s not going to make that slow march to class until the day she doesn’t, her kids won’t be any less traumatized if she dies suddenly, without warning. She can only impose her will for so long.

Sally Draper

I’m finding it difficult to think about Sally without crying.

A few weeks back Sally told Don that she didn’t want to grow up to be anything like her parents. She’s been able to see their faults for a long time now, first Betty’s and then, quite suddenly, Don’s, and she’s still young enough to believe that knowing who she doesn’t want to be will be enough to prevent her from becoming that person. But Sally is already too much like both of her parents, her fate in that regard has already been written. Don told her as much in “The Forecast.”

And here in “Person to Person” we say goodbye to Sally as she fulfills that fate. She comes home to take her mother’s place as the head of the household, already making decisions about what’s best for Bobby and Gene once Betty is gone: consistency, sleeping in their same beds at night. Betty told Don that they would need a woman looking after them and while she meant her sister-in-law, a woman she openly dislikes, Sally is stepping up instead.

Sally is the one sending Gene to watch TV when important things must be discussed, she’s the one talking to Bobby about what’s really happening, and showing him how to make dinner. She’s the one that tells Don that Betty is dying. Tells him to listen, because she’s thought about this more than he has. She’s had the time. Like her mother, she’s the one telling Don not to come home.

Our final shot of Sally is a tragic one: she’s at the sink in the background, washing dishes while Betty, still smoking, fades in the foreground. She’s given up school and Milan and who knows what other secret dreams she may have had, or at least she has deferred them for awhile, and soon Betty will be gone, and Sally will take her place as the grieving daughter.

Maybe when Don comes back to write that Coke pitch he also steps up as a father, but it’s hard to believe he can change now, we’ve seen him pass over so many opportunities. He will probably always be, at best, an inconsistent parent. So the weight will fall to Sally. And it’s a sad ending, especially alongside so many hopeful ones. I wanted more for her.

Mad Men 7×13: Happy Mother’s Day

Towards the beginning of this season of Mad Men, in “A Day’s Work,” Sally went to a funeral for a friend’s mother. She had never been to a funeral before, was intimidated and scared by the whole thing, even as she sat on her bed at Miss Porter’s, smoking a cigarette and claiming “I’d stay here til 1975 if I could get Betty in the ground.”

She was sitting in the same spot last night when her step-father told her Betty was dying.

Much of Mad Men has been the story of Sally’s loss of innocence. She has watched her parents misbehave, use their looks and their charms to their advantage. She’s seen them fight with each other and with her step-parents. She caught Don sleeping with the downstairs neighbor, and Marie Calvet with Roger. As a little kid she got drunk in the Sterling Cooper offices when her father took her to work. Sally has never stopped observing the world around her, even when it has upset her, or when she didn’t like what she saw. It’s forced her to grow up ahead of schedule, but deep down she’s still a kid, only 16 in the fall of 1970.

If Sally’s development has been accelerated, Betty’s is arrested.

When we met Betty Draper she was grieving her recently deceased mother, so distraught that her hands shook and she drove her car off the road, with Sally and Bobby in the back seat. When she went to see a psychiatrist he checked in with Don after her sessions, debriefing and diagnosing to her husband, rather than to her. Betty had once had a great deal of potential, with an education from Bryn Mawr and a modeling career, and a skill for speaking Italian. Fitzwilliam Darcy would probably have called her accomplished. But she chose to marry a man her parents disapproved of–a man she didn’t know was lying to her about everything from his affairs to his identity–and move to the suburbs to have his children.

And that left her feeling stuck–stuck in childhood, stuck in her marriage. She couldn’t grow up while still being treated like a child, couldn’t pick her career back up with Don working in the same industry. She had regrets. She had resentments. They manifested as anger and as numbness. She spent much of the first season fascinated by Helen Bishop, the divorced woman down the street. She saw in Helen a choice she couldn’t make for herself, an independence she did not possess.

Even when Betty did eventually leave Don, it was to immediately remarry. Don may not have loved Betty enough, he certainly contributed to her infantilization, but Henry loved her blindly. He didn’t care whether she was pregnant with another man’s child, or overweight, or whether she was as picture-perfect as she’d been in her modeling days. He didn’t care that she could be petulant and child-like. He directed her more like a parent than a husband, in what to do and what to think and how to raise her children. Betty may have found a way out of her first unhappy marriage, but she didn’t find anything resembling independence.

But the revelation that Betty is sick, and not just sick but dying, with maybe 9 months to a year left if she receives treatment, has knocked Henry down, too. He goes to Sally for help, lays that burden of convincing Betty to try to fight her lung cancer on Sally’s 16-year-old shoulders. He tells her she can cry, but then he breaks down himself before she has the chance. He asks Sally what he’s going to do without Betty when he should be more concerned for how she’s feeling. He drags her home to literally take her mother’s place at the head of the dinner table, with her baby brother in her lap.

And Betty hands her an envelope with instructions for what to do with her body. Ever concerned with her appearance, Betty has already set the dress aside, told Sally which lipstick she wants and how the mortician should style her hair. She says that Henry will be useless and she’s right, he already is, so yet another adult burden falls to Sally. It’s another hard shove in the direction of adulthood.

At the beginning of “The Milk and Honey Route,” before Betty’s lung cancer had made itself known, Sally was on the phone with Don, talking about school, and his road trip, and going to Spain. It’s the only scene in the episode where Sally’s treated like she’s still a kid. Their conversation is friendly, one of the friendliest we’ve seen between them in years, but Don is also very much her father, wishing she had quit field hockey before he bought her the equipment and asking her to sell it, telling her she has “no idea about money” (a phrase that’s not all that different from something Betty said to him once, the way she knew that he grew up poor). It was Don that Sally opened up to about the funeral back in “A Day’s Work,” the “awful” funeral, where her friend’s mother was yellow in a bad wig.

Sally needs a parent like Don right now, someone who can still look at her and see a teenager. Don has worked to be more honest with Sally since the end of season 6, telling her the truth about Dick Whitman, and apparently keeping her informed about this post-McCann road trip, there is more heft to their conversations now, but he still, for the most part, expects 16-year-old things of her. But Don is off in Kansas, sitting at a bus stop 3 million dollars and a Cadillac poorer than he was at the beginning of the season. If Don isn’t coming back, if Sally doesn’t have him to lean on, then what will become of her now?

Mad Men 7×12: Transitions

The transition from SC&P to McCann-Erickson is not without some growing pains.

The former SC&P secretaries are mothering Don, making sure he can find his way from the lobby to his new office, whether that’s Beverly making sure he knows what floor he’s going to or Meredith coming to meet him at the elevator, reminding him that he can’t be late, that he can’t take naps now that Jim Hobart’s back from vacation. (There’s lots of talk about floors in this episode, everyone save Peggy divvied up around the building, unable to provide each other with support.)

The hallways at McCann are dark and claustrophobic, full of new people heading every which way–the opposite of the bright, modern space that housed SC&P. Don’s office is reminiscent of the one he had back at Sterling Cooper, in the first three seasons, with the wood paneling and his desk off to the side, but he doesn’t seem comfortable in it. Meredith asks him if the smell has improved, and he fiddles with the windows, which emit a high-pitched whistling noise from the wind 19 floors up.

But Don seems happier once he’s meeting with Jim Hobart and Ferg Donnelly. Hobart appeals to his ego, refers to Don as his White Whale. He even claims that he bought a small agency in the midwest just so he could get Don the Miller account. They’re looking to brand what will eventually be Miller Lite. Hobart encourages him to introduce himself and nearly swoons when Don says he’s “Don Draper from McCann-Erickson.” He seems genuinely thrilled to have Don on their team at last.

This is all just an ego-stroke, though, as Don learns when he shows up to the Miller meeting and finds out that half of McCann’s creative directors have been invited. Ted Chaough is there, looking as serene as he was last week when Hobart promised him a pharmaceutical account. It’s clear he’s been fed the same lines as Don, about his value to the agency, but he doesn’t seem bothered by the discovery that he’s just a cog in the McCann-Erickson machine. He fits right in in the Miller meeting, but Don still wants to be something special, he wants to be the myth he spun for the reporter back at the beginning of season 4. When he gets up and walks out of the meeting it’s a move we’ve seen before, just like his subsequent disappearance (to Racine, Wisconsin, though he neglects to tell even Meredith that he’ll be out indefinitely) it’s the sort of thing that helps build up the Don Draper Mystery, but no one in the meeting even looks up. They’re too busy working.

Meanwhile, Joan’s dealing with the same overt sexism that plagued the Topaz meeting back in the mid-season premiere.

Unlike at SC&P, Joan’s got a window office at McCann, a status symbol that turns out to be just as fake as Don’s ego-stroke. Two female copywriters show up before she’s even settled in to try to attach their names to her client list, and the men at McCann are pigs in every available flavor. One of the account men from the Topaz meeting, a man Joan technically outranks, torpedoes a call with Avon after failing to read Joan’s briefing, gets mad at her for getting mad and then sneers “I thought you were gonna be fun” as he storms out of her office; when she gets him off her business by going to Ferg Donnelly she finds herself rebuffing Ferg’s repeated advances; and when she goes to Jim Hobart to try to remove Ferg she’s informed that she’s worth nothing to McCann, that she can either walk out the door with only fifty cents for every dollar they owe her or she can bring a lawsuit they’ll fight, but either way she’s walking out of Jim Hobart’s office and he doesn’t want to so much as hear her name.

Hobart implies that Joan did nothing to earn her SC&P partnership, suggests that maybe it was left to her in a will, but Joan sacrificed more for that title than anyone else. She’s fired up to fight for every penny of her half million dollars because of what she did to earn them, to metaphorically burn McCann-Erickson down, the way she wanted to in “Severance,” with references to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and Betty Friedan, and it’s only Roger, who knows exactly how she ended up with a partnership, who can convince her to take the $250,000 and walk out the door. Joan leaves McCann with a lot of money, her rolodex, and the wind knocked out of her sails.

It was Roger that walked into Sterling Cooper with his name already on the door, and it’s Roger that’s having trouble leaving it behind. Peggy finds him skulking around, playing ominous music on an organ and looking for ways to get drunk instead of heading off to start his new job.

Peggy’s still at SC&P because McCann mistook her for a secretary and didn’t have an office ready. She spends the whole episode trying to walk the line between not accepting less than she deserves, like Joan, and not wanting to make too big of a fuss. She doesn’t want her secretary to go running to Don with the problem, but she wants someone to stick up for her. She doesn’t want to start her time at McCann working from a secretary’s desk, but she can’t accomplish anything from the SC&P offices, where first the power goes out and then the phones. She finds Roger just after her secretary informs her (from the same hall payphone where Ken discussed the life unlived with Don) that they’ve got an office for her but she’ll have to work from a drafting table until her furniture is delivered.

The scenes between Roger and Peggy are where the episode shines brightest. They get drunk on a bottle of vermouth and Roger offers Peggy the painting that Bert Cooper had hanging in his office, the one of “an octopus pleasuring a lady.” She claims she can’t hang it in her new office because the people at McCann won’t take her seriously. “You know I have to make men feel at ease,” she tells Roger. The patient way she rode out the unfiltered sexism in the same Topaz meeting that inflamed Joan, the image of her on the Playtex exec’s lap back in “Maidenform,” the way she’s handled the bungled move to McCann…Peggy’s been putting men at ease to get her way for years, but Roger doesn’t see the point.

Roger’s not bothered by women in the workplace. He’s of a different era, yes, occasionally old-fashioned, but he’s long been dependent on Joan, bullied by his secretaries, and he was the one who gave Peggy her own office back in season 3. He responds positively to assertive women. He tells Peggy a story about cool water on a hot day, and how he almost missed out on what he wanted because he was scared of the jump. Peggy tells him that everyone has regrets, but this wasn’t a regret, he just needed someone to push him. Roger does the opposite for Peggy of what he did for Joan: he gives Peggy the necessary push.

And when we see her striding into McCann, cigarette lit, sunglasses on, in what is instantaneously one of the defining shots of the series, it’s clear that Peggy won’t be taking 50 cents on anyone’s dollar (or 70 cents, for that matter), and that despite what Ferg may have told Joan earlier in the episode, McCann will not be holding Peggy back. If someone’s going to burn McCann-Erickson to the ground it’s going to be Peggy, and she’s going to do it from the inside out.

Mad Men 7×11: the Life Not Lived

Mad Men’s first season ended with Peggy receiving a promotion from secretary to junior copywriter and then promptly giving birth to a baby she didn’t know she was carrying. The decision she made after that, to carry on with her career and give the baby up for adoption, has come to define her character for the rest of the series.

Peggy didn’t arrive at Sterling Cooper with big dreams about a career in advertising. The girl we met in the pilot was fresh out of Ms. Deaver’s Secretarial School, naive, smiling at the suggestion that she might meet a husband at her new job. Peggy wasn’t thinking about pursuing copywriting, she was coming on to Don on her first day, enjoying the attention of Ken and Kinsey and, of course, Pete. But by the end of the first season Peggy had started to see a different life for herself. She walked through the door that Freddie Rumsen opened for her when he heard potential in the phrase “basket of kisses,” and she found a dream she hadn’t expected.

Everything Peggy has done since has been in pursuit of that dream. Whether she was taking Joan’s advice to “learn to speak the language” and “stop dressing like a little girl,” or watching and emulating the way Don speaks back to clients, she has consistently directed herself towards the future she laid out for Don in last week’s episode, the one where she’s SC&P’s first female creative director, succeeding the man who helped get her there. The future where she’s created a catchphrase and attained the fame that comes along with it. The future where she’s built something meaningful in advertising. Peggy’s dreams have only grown as the world has opened up to her. The world of her career, anyway.

Because alongside her ascent in her professional life we have seen the descent of her personal life. Peggy’s mother and sister have drifted off-screen over the years, as she moved out of Brooklyn and away from her Catholic upbringing. She’s had a few boyfriends who weren’t quite the right match, a couple of affairs with older male co-workers. She went on her most promising date in seven seasons a few weeks ago and came out of it more embarrassed than excited. The most significant relationships in her life seem to be with Don, her mentor, Pete, the man who got her pregnant and her uneasy ally, and Stan, her best friend, maybe the only real friend she has at SC&P.

Contrast Peggy’s life to Trudy Campbell’s.

The morning after Pete was seducing Peggy, way back in the pilot, he was marrying Trudy. Trudy’s path was far more traditional than Peggy’s. She made what she believed to be a good match, marrying a man she loved, with an impressive family name, and a career he was passionate about. She took on the role of housewife with enthusiasm.

But gradually the reality of a marriage to Pete wore away at her. Their years of infertility, his pride and infidelity and dissatisfaction, and the temper that is always close at hand, all brought their marriage to an end before the 1960s were over. Like Helen Bishop back in season one, Trudy is a divorced single mother in the suburbs, a woman who can’t get her daughter into an elite preschool, the object of her friends’ husbands’ attention. She’s a throw-back.

In last night’s episode, “Time & Life,” Peggy told Stan about her decision to give up a child, the first person we’ve seen her tell since Pete, all the way back in season 2. She tells him because they’ve been casting kids all day, pulling her out of her comfort zone, and because he’s just witnessed her throwing down with a stranger over her parenting methods. But she also tells him because she’s reached another turning point in her career, the opportunity to either replace SC&P with another small agency or go big at McCann, reframe her future on a grander scale, and it’s got her looking backwards at where she’s been. At the life she exchanged for the one she got.

The theme of the unlived life has been coming up again and again this half season, and now it’s Peggy’s turn to look around her and see what could have been. It’s hard to imagine Peggy as the stage mother she confronts in “Time & Life,” the encounter that prompts her confession, but the audience is privy to something a bit closer to Peggy’s might-have-been: the scenes between Pete and Trudy.

If Peggy had chosen differently at the end of season 1, if she had kept her baby and shamed Pete into leaving Trudy and starting a family together, as she suggested she could have when she told Pete what happened, she still wouldn’t have ended up as Trudy precisely. Their personalities are different, their backgrounds are different, the way that they relate to Pete is different. But Peggy would still have been a woman who set aside her career to be a mother and a housewife. Pete would still have been angry and unhappy and resentful. There’s every reason to believe that Peggy too would have ended up a single mother.

But that’s the thing about the unlived life: there’s no way to know for sure. Peggy made a choice and in making it it became her only choice, she can’t go back on it. She can only look ahead to her next decision, in this case a lateral move or a big leap forward. Could the Peggy we know have decided to do anything but leap?

Mad Men 7×10: History Repeating

We spent last week with Don Draper wallowing in the past, repeating old patterns, steadfastly refusing to change. And then this week’s episode pulled the apartment out from under him–maybe Don doesn’t want to change, but the universe doesn’t always give you that much choice in the matter.

Don comes up blank when Roger asks him to write a speech on SC&P’s future. He’s not a guy that thinks very far ahead, it’s Don’s inability to look past what’s immediately in front of him that causes him to act so impulsively, and to repeat so many mistakes, so it’s hardly surprising that he doesn’t know where to start with Roger’s speech; he organizes his thoughts to start writing by requesting an SCDP press release from 1963, and he quotes the Gettysburg address, “four score and seven years ago.” Don’s tasked with looking forward, but instead he’s reaching back, rooting around for something he can use. And when that doesn’t work he starts taking an informal poll.

Ted, such a sad-sack these days, just wants to land a pharmaceutical client. He talks about it like it’s as wild a fantasy as running off to join the circus, but Don finds his thinking disappointingly small. Peggy’s hoping for big clients, too, but her dreams are more for herself than for SC&P at large. She wants to be the agency’s first female creative director–she wants Don’s job. And she wants acclaim, fame; while Don sneers at that a bit she’s not ashamed to want it, or ashamed to confess to wanting it. And she wants to build something meaningful; she’s still an idealist at heart.

Meredith thinks the future will be like the World’s Fair.

And it’s not just the people Don asks that are looking ahead. Lou Avery, out in the LA office, is pursuing his cartooning dreams with Hanna-Barbera. Joan is exploring a potential relationship with an older man. Betty is getting ready to go back to school. Glen, having flunked out, is exchanging an education to go fight in Vietnam. 1970 is rolling along, carrying everyone with it. Everyone except Don.

Towards the end of the episode Don finds himself at dinner with Sally and three of her friends from school, asking them what they want from the future. One wants to be a senator, another a translator at the UN, the third just wants to live in New York. The world is wide open to these girls in 1970, far more so than it was for Peggy or Betty or Joan back in 1960. None of them expect to become someone’s secretary, they aren’t planning futures as housewives. Only Sally is reluctant to express a hope for the future, claiming she just wants to eat dinner. Even her summer plans are vague, once she gets back from her teen tour. Like her father, she’s not particularly interested in looking past what’s directly ahead.

But when she’s alone with Don she opens up. “I want to get on a bus, get away from you and Mom, and hopefully be a different person from you two.” Of course, this is exactly what Don tried to do when he was about her age. Like Glen, Dick Whitman signed himself over to the army. He went off to the Korean War to get as far away from his family and his childhood as possible, and he reinvented himself with the help of another man’s identity.

In theory Don Draper could not be farther from Archibald Whitman, living in a penthouse on the Upper East Side instead of poor on a farm in Illinois. But Don’s broker is quick to point out that his penthouse is “an $85,000 fixer-upper,” hard to sell because it’s still sitting empty from when Megan’s mother cleaned it out, with the wine stain still stretched across the bedroom floor. Don knows, deep down, that he didn’t make it quite as far from rural Illinois as he wanted to. “You are like your mother and me,” he tells Sally. “You’re gonna find that out.”

Because while everyone else is looking forward, ahead to what’s next, Don sees a circle, the wheel from his Kodak pitch back in season 1. He sees that Sally is like him and that he’s like his father. He sees the word “love” still cropping up in taglines, when back in the pilot he told Rachel Katz “what you call love was invented by guys like me to sell nylons.” He sees Peggy and Pete still squabbling in the office hallway.

And we can see Joan falling into the same traps with Richard that she did with Roger, and Betty in the kitchen with Glen, still blurring the lines of what’s appropriate to give him comfort. Maybe Don doesn’t feel the need to change because he sees everything cycling back around, the future returning to meet up with the past. Maybe he believes that if he stands still, or walks the other way, eventually he’ll cross paths with the rest of the world. But the universe isn’t interested in giving him that option.

As the episode ends we find Don alone again. Single again, without his kids again. He’s shut out from his own apartment, even, where a growing family is also looking towards their future, starting fresh in Don’s home. Don is getting left behind.

Mad Men 7×09: The Illusionist

“I know it’s not real. Nothing about you is.” – Megan Draper

The opening scene of tonight’s Mad Men felt, for just a split second, like a time warp back to the first few seasons. There was Don Draper, in his casual weekend polo, in a suburban kitchen with his kids, making milkshakes. And then in walked Betty, elegantly dressed, making casual conversation–the four of them, Don, Betty, Bobby and Gene, looked like a family, Don’s long-sought portrait of domesticity.

And then Henry Francis stepped into the kitchen, dressed to match his wife, and Don became the man on the outside looking in.

Don Draper has always had a vision of the life he wants to lead. He started constructing it as a child, the boy who built normalcy out of the taste of a Hershey bar. He’s been filling it out ever since, taking on a new identity, conning his way in the front door of Sterling Cooper, marrying the model in the expensive fur coat and then turning their life together into the picture of domestic bliss that might show up in one of his ads (that did show up in the Kodak pitch back in season one, “the pain from an old wound” he spoke about over slides of his supposedly happy family), with the little girl and the little boy, the dog and the house in the suburbs.

And when that didn’t work out, when his family cracked to pieces, he tried to start over with a different script. He followed Roger Sterling’s example and married his young secretary, told her his big secrets so they wouldn’t be lying in wait, traded in the suburbs for a fancy apartment in the city. And still it didn’t work out.

Because Don always forgets the same thing: the wives he’s using as props are the central characters in their own life stories, whether that’s Betty struggling through a combination of depression and arrested development in the wake of her mother’s death, or Megan realizing she’s not ready to give up on her dreams just because she’s married. Their lives continue when Don leaves for work in the morning, they don’t sit in their well-appointed living rooms, in suspended animation, awaiting his return.

Tonight’s episode was titled “New Business,” but it was really just more of the same: Don playing like a child with a dollhouse. Megan’s moving her things out of the apartment, so he’s stalked Diana, the waitress he met in last week’s episode, the one who reminded him of someone (His mother? His step-mother? The ghost of Rachel Menken? Sylvia? Megan? Midge? Miss Farrell? Take your pick from Don’s long list of sad brunettes) to her new job and brought her home to take Megan’s place.

Don’s quick to reassure Diana that he’s had the time to move on from his marriage, that he’s ready for another commitment, but he fails to take her emotions into account, just as he did with Betty, just as he did with Megan. In Diana he sees a kindred spirit, a woman who has just gotten divorced, who has left behind her ranch house and her two car garage in Wisconsin for a new life in New York City, and he thinks, because he believes he is ready to start fresh, that she is too. But Don’s not listening (literally not listening. When she refers to a twinge in her chest he hears her reciting that Kodak pitch back at him, “a pain.” “It’s not that,” she says), not to her grief over a child she lost, or to her general ambivalence towards the city (a city that is as crucial to his self-image as the wife and kids. “I always wanted to live here. It was in all the movies, all the magazines,” he tells Diana. Don’s repeatedly flirted with the West as a place to escape, but the stories he’s built for himself have all been centered around New York City). He’s looking for a new prop to lie next to him in bed at night, to wear his ex-wife’s coats, to take on those client dinners he discusses with Pete. He doesn’t want a new character in his life, a woman with her own motivations. The idea that the people around him might be following a different script presents too wide of a window for complications.

Mad Men is often praised for its attention to detail, the meticulous costuming and set-dressing that brings the show to life, but that careful construction is as much about Don as a character as it is a part of the show itself. I wrote last year about the way Don put on a suit to meet Dawn at his door for a few minutes, even though he had no reason to bother with the ruse. He does the same in “New Business,” but it’s Diana at the door this time, and it’s 3 am, and this is whatever you would have called a Booty Call in 1970. When she questions the suit he claims he’s vain, but the truth is the illusion is cracking. He doesn’t know what to wear to meet this woman at his door at 3 am. The pristine white carpet in his bedroom is scarred with the red wine we saw spilled last week. He’s playing golf in his suit and tie, with rented clubs. It’s the spring of 1970 and he still doesn’t know about the Manson family. His kids live in another man’s house, fill out another man’s family, and their bedroom in his apartment is just negative space, a frame onto which Diana can project her own grief.

At the end of the episode Don is standing alone in an empty living room. Megan’s mother has taken all of the furniture. The house in Ossining was decorated by Betty, down to her chaise lounge crowding the living room, and as Don told Diana tonight, the apartment was decorated by Megan. But Diana has turned Don away, he has no one to decorate the set for the next show he puts on, whatever that might be. He has no script, no co-stars, no props, breathing or inanimate, he’s even out a million dollars. So the questions coming out of “New Business” are these: where does Don Draper go next? Towards what vision does he rebuild? Will it finally resemble the truth under the Don Draper facade? Was that the last we’ll see of Diana? (And please, oh please, will Sally be back next week?)

Mad Men 7×08: “I Want to Burn This Place Down”

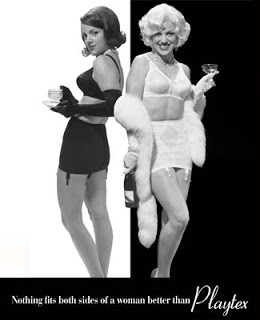

Once upon a time, in season 2’s “Maidenform,” the creative department of Sterling Cooper proposed a campaign to Playtex: Jackie and Marilyn as two sides of one woman. The men pointed at different women around the office, assigning them to a category. This secretary was a Jackie, that one a Marilyn, another a Jackie, Joan certainly a Marilyn. Peggy, they said, was neither (“Gertrude Stein”). At that point, as their first female copywriter, Peggy had already left behind the typical roles for women in the Sterling Cooper offices. It was like she no longer counted.

Once upon a time, in season 2’s “Maidenform,” the creative department of Sterling Cooper proposed a campaign to Playtex: Jackie and Marilyn as two sides of one woman. The men pointed at different women around the office, assigning them to a category. This secretary was a Jackie, that one a Marilyn, another a Jackie, Joan certainly a Marilyn. Peggy, they said, was neither (“Gertrude Stein”). At that point, as their first female copywriter, Peggy had already left behind the typical roles for women in the Sterling Cooper offices. It was like she no longer counted.

Peggy’s fight on Mad Men has always been to be taken seriously. To be seen as more than a little girl playing in a man’s world. She didn’t go to college, but to Miss Deaver’s Secretarial School. She worked her way up because the right people noticed what she could do, because she had good teachers and, most of all, because she decided what she wanted from her life and wouldn’t let anyone take it away from her. She learned to be firm, to stand her ground, to say no. She watched Don and she tried to emulate him until she could get her own way. It made her a force as a copywriter. It also meant she had to sacrifice a great deal in her personal life, giving up repeatedly on loves that weren’t quite right, and giving up a child–and its domestic trappings–to single-mindedly pursue her career.

Joan isn’t seen as a little girl at all. Her battle has been with her own figure, and the expectations the world places upon it. When we first met her, in the pilot, she had more power than any other woman in Sterling Cooper’s offices. She looked at Peggy like a puppy she could train. She was pleased with her life, with her own understanding of how the office worked, with her ability to do her job well. Professionally, she didn’t want anything more. And over the years since that’s changed. She got married and realized maybe that victory wasn’t what she wanted. She became a single mother and realized she’d have to provide for her son. She took on new responsibilities at work and realized maybe there were opportunities she hadn’t seen before. Joan watched Peggy’s ascent and started looking up her own ladder, discovering it had more rungs than she’d previously thought.

But when Peggy called a bunch of used tissue a “basket of kisses” in front of Freddie Rumsen he saw potential. When Joan excelled in the media department Harry Crane saw it as a job so easy even a secretary could do it.

“Maidenform” is the episode where Peggy starts to figure out the path that will work for her at Sterling Cooper. She’s finding herself shut out of meetings on the Playtex account. She’s not invited to casting, nor to the after-hours partying where the real business gets done. And she goes to Joan for advice. “You’re in their country. Learn to speak the language,” Joan tells her. And: “You want to be taken seriously? Stop dressing like a little girl.” At the end of the episode Peggy shows up to boy’s night at the strip club with the Playtex executives. She wears a low-cut dress and her hair down. She sits on an executive’s lap and she smiles and she plays along with the men. And over the years since she’s excelled because she has learned to speak the language. She’s given up her old spoil-sport attitude toward the ways the men in the office behave and she’s learned to talk back. Her clothes have become more adult and more professional. She has asserted herself by defying people’s expectations of her.

Meanwhile, Joan has always used those expectations to her advantage. She’s seemed to grow stronger from them. She knew that she could swing her hips or wear the right dress and get her way with just about anyone. And that power culminated in Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce pimping her out to a Jaguar executive in exchange for a partnership.

In that partnership Joan found a way to provide for her son. She found self-sufficiency beyond anything she’d ever imagined. And she’s also leveraged it into more fulfilling work. She’s got her own accounts. She’s got new challenges. She has a job that shouldn’t have anything to do with her physical assets, but with her brain and everything she’s learned watching business happen in the Sterling Cooper (Draper Pryce) (And Partners) offices over the years.

In the meeting that Peggy and Joan take with the McCann Erickson executives in last night’s episode, “Severance,” they are the only representatives for SC&P. Don’s not there, nor Pete or Ken or Harry. They sit across the table from three men who will listen to what they have to say, sure, they’ll even approve the request for support with Topaz Pantyhose. But first they’re going to make a whole bunch of jokes, they’re going to comment on Joan’s breasts and make references to her panties. They see the novelty of taking this unusual meeting with two women, and not the everyday of Peggy and Joan’s lives, working in this office.

Peggy has sat through these meetings for years. She’s rarely been targeted sexually, at least not the way Joan has, but she’s had to fight for men to take her seriously in her job. It’s wasn’t enough to gain the respect of her co-workers, because the nature of the industry required the clients to listen to her, too. Her ability to roll with the daily micro-aggressions, that advice she took from Joan back in “Maidenform,” to learn to speak the language, allows her to keep her cool in that meeting. To laugh a bit at the inappropriate jokes at her expense, and to keep chugging through her presentation until the men are ready to listen to her. But Joan has run out of patience for being treated like a walking bra. She’s not an office manager anymore. Topaz is her account. She expects more.

But over and over again Joan is reminded that people will refuse to look past her appearance. Hell, she’s a partner, but she has to wait with the models in casting to get an audience with Don (who, like the rest of the men in the office, has had his business hours consumed by the effort to find a beautiful woman to walk around in nothing but a fur coat and show off her smooth skin). And then, in the elevator after the meeting, so much rage boiling in her blood that all she can say is “I want to burn this place down,” Peggy twists the knife, blaming the comments on the way Joan dresses and then, in frustration, saying, “You’re filthy rich. You don’t have to do anything you don’t want to.”

Of course, Peggy doesn’t know the price Joan paid to become a partner, the price she paid for her wealth. She’s seen men treat Joan like a sex object for years, and she’s never seen Joan angered by it. Peggy and Joan have both come a long way since they met in 1960, but they struggle to see past their initial impressions of each other. Joan still sees Peggy as naive, and Peggy sees Joan as worldly, and to a certain extent each of them envies the other. But Peggy is taken more seriously now. It’s hearing Stevie repeat back the compliments Mathis paid her that starts to shift her attitude on their date later in the episode, the respect that this man who works under her has for her, that he’d pass it along to his brother-in-law, makes her warmer, more open. Joan has not yet reached that point. Joan can’t even see it.

So instead she goes and spends some of that money she worked so hard to earn. She goes to the department store she once worked in, back when she was trying to support the husband who couldn’t support her, and spends her own money on dresses and boots that will show off the figure men and women can’t look past. She refuses the offer of a discount because she doesn’t need it, doesn’t want it.

She’s filthy rich, after all. She doesn’t have to take a call from a jerk at McCann Erickson.

“Just tell the truth.”

The realization that your parents are human beings in their own right, with their own histories and secrets, that they are the central figures in their own lives, happens to everyone eventually. It’s a gate you go through on your way to adulthood, one that locks behind you. Once you see someone you love so purely as a three-dimensional person you’re better off, I think, you know them better and you know yourself better, but it’s not an easy thing. Nothing about growing up is easy.

Sally Draper’s image of her father has grown more detailed with every passing season of Mad Men, the lines sharper, the shades darker. She is a bright and observant girl, and in the early seasons Don was often his best self in her presence. He wasn’t a good man or a good husband, but he tried to be a good father, and in Sally’s eyes he has often seemed a better option than Betty (this week, full of hyperbolic teen bravado, Sally claimed she’d stay on at boarding school another 6 years in exchange for her mother’s death). Let’s not forget the time she ran away from the Francis home and turned up at Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce because she wanted to live with her dad. Sally is Don’s, through and through.

But the pedestal on which Sally placed her father has been crumbling for awhile now, especially since she caught him in flagrante delicto with the downstairs neighbor last season. While season 6 ended with Don taking his kids to see where he grew up, and to presumably tell them the truth about Dick Whitman, it’s clear when he arrives back at his apartment in “A Day’s Work” to find Sally waiting on the couch that they have not been able to rebuild the bond they once shared. Sally is still angry and Don doesn’t know how to fix it.

Sally’s anger is renewed, though, over her discovery of yet another lie: Don’s not going to work these days and someone else has taken up residence in his office. When Sally gives Don a chance to come clean he lies again, and poorly. He’s still learning just how much his daughter takes in, how watchful she is, and if Dawn hadn’t called him he might not have learned about Sally’s revelatory visit to SC&P.

Don has always been overly concerned with the facade, the image of Don Draper that his double life necessitated, and he isn’t ready to let that go just yet, even as more and more of the people in his life have been let in on his Big Secret. He may be spending his days sleeping till noon, drinking, and stuffing his face with Ritz crackers in front of reruns of The Little Rascals, but he’s as slicked and shined and put-together as ever when Dawn comes by to fill him in on his calls and accounts. He doesn’t want her to see him slip, even though he knows she knows he’s slipping, even though he’s loosening his tie as soon as she’s out the door. For an audience, even an audience of one, he has to be Don Draper, and that’s more than just a name.

So he tries to put on the Don Show with Sally as well. He hand-waves the illness he claims has him home in the middle of the day and offers to drive her back to school, takes it as an opportunity to talk to her (to talk to anyone), not to mention a project to fill some of his time. He writes Sally a note of excuse (“Just tell the truth,” she tells him, in the dearest, most English-Major-y line of the night) and they hit the road for a little father/daughter one-on-one time. But Sally’s not having it. She knows her father too well now.

In fact, by this seventh season Sally knows more of Don’s secrets than anyone else–anyone but Don himself, at least. She knows about Dick Whitman, she knows about Don’s affair with Sylvia, and now she knows that he’s been forced out at SC&P, and why. The moment where he opens up to her about what happened in the Hershey meeting is like a sledge hammer hitting the brick wall between them: it’s not going to knock the whole thing down, but it’ll let a little light through. It’s at least enough to get Sally to eat something.

It would be ludicrous to claim that Mad Men has any single central story, but one of its strongest throughlines over its run has been Sally’s coming of age. She’s wise beyond her years, yes, but she’s not all grown up yet. She doesn’t know how to dress for a funeral, can still be a little intimidated and dazzled by her father’s suggestion that they skip out on their restaurant bill. Sally is a kid who has seen too much, perhaps television’s most solid example of Philip Larkin’s “This Must Be the Verse,” but she’s not as worldly as she sometimes seems. Much like her father, she knows how to put on an act.

Don thinks his image is all he has left, the facade of Don Draper: Ad Man, but all he really needs to get through to Sally is a little bit of honesty. She may think it’s more embarrassing to catch him in a lie than it is to let him lie to her, but that doesn’t mean she’ll play dumb and go back to being Daddy’s Little Girl, and while her methods to get her dad to open up aren’t particularly sophisticated, they are effective. When Sally calls to check in, her friend Carol says, “at least the trip was worth it.” She’s talking about shopping, but Sally’s got more on her mind.

But Sally’s not the only one that gets something out of Don’s decision to open up, Sally gives something back. She eats a tuna melt, tells Don about the funeral, and, most importantly, uses her last moments with him to tell him she loves him, throwing the words at him as she’s jumping out of the car, like she’s scared to let them go.

This week’s closing moments were essentially the opposite of last week’s. We left Don alone again, sure, but rather than the self-pitying, lonely Don, out in the cold, trapped by his own lies, this week Don had hope, he had the capacity for redemption. He told the truth and Sally loves him, maybe she even loves him more. Maybe Don is finally learning that the truth can set him free.

Top 10 TV Shows of 2012

Better late than never, here’s my run-down of my personal top 10 television shows of 2012. (This list was created on a weird, internal sliding scale between “best” and “favorite.”):

1. New Girl (FOX)

Around the middle of its first season, when New Girl finally figued out how to do what it had been trying to do, watching it became an almost transcendental weekly experience. What the writers (and Max Greenfield) had done for Schmidt since the beginning–reveling in his specificity–they figured out how to do with the rest of the cast. They gave Jess a platform to claim her own adorkability, to stand up and say, “I rock a lot of polka-dots.” They figured out how to work with Jake Johnson’s gift for grump, so that Nick’s prematurely old nature still fit with the rest of the ensemble. And they weirded Winston up a little more every week, showering him in bizarre anxieties and pairing him with characters that made him pop. By the time the show arrived at the Fancyman arc, the characters were well-defined enough that Jess wouldn’t get buried under the personality of an older boyfriend, and the roommates could spend most of an episode playing an incomprehensible drinking game without the show feeling shapeless.

I hope that, as New Girl goes forward, they’ll figure out how to tell more stories focused on Winston, and I’d like to see them expand the female cast a little–it was nice to see Jess’ friend Sadie return a couple of weeks ago, and my newfound non-hatred of Olivia Munn has made her a mostly welcome addition to the cast. But I am largely complaint-free when it comes to New Girl. (And honestly, any show offering the kind of chemistry that New Girl has with Nick and Jess–and it’s hitting Sam and Diane levels these days–would probably top my list. They’re electric.)

2. Breaking Bad (AMC)

Breaking Bad is the sort of tv that leaves me literally gasping for breath. It’s suspenseful, sometimes terrifying, often maddening, but it grounds itself in its most ordinary moments, letting the audience learn its characters as people, to make them that much more horrifying when they’re at their most monstrous. Breaking Bad works because it doesn’t just ask you to believe in its world, it shows you why you should. It takes a bumbling loser of a man out of a moment of desperation and, over the course of 5 seasons (though only one year in its internal time), turns him into an over-confident ruler of an already crumbling empire. It shouldn’t work, but it does, because Walter White has laid all the traps for himself, we’ve watched him do it, and he only trips them out of his own hubris.

3. Bunheads (ABC Family)

You’ve already heard me go on about my affection for Bunheads, for the warmth and charm and patter of Amy Sherman-Palladino’s latest creation, and I don’t have that much to add on the subject. Bunheads made this list (and made it so high) because it’s television that fills me up in the best possible way. It’s not an ooey-gooey sweetheart of a tv show (Sherman-Palladino’s creations are far too cynical for that), but it offers cultural sustenance. And surprising, delightful dance numbers.

4. Hart of Dixie (The CW)

Maybe the most appealing thing about Hart of Dixie is the way it takes the inner lives of its characters seriously, even when it doesn’t necessarily take itself all that seriously. I’ve described Hart of Dixie, again and again, as charmingly goofy, and that’s absolutely true, but it’s also got a bit of meat on its bones. The characters, particularly Zoe Hart, the confident, sex-positive, deeply flawed main character, and Wade Kinsella, who could so easily be written off as a clichéd bad boy, are richly imagined and well portrayed. The cast is talented, AND they all have CW good looks, and the town of Bluebell, though perhaps built from the wreckage of a handful of other little TV towns that came before it (it’s literally filmed on the old Stars Hollow sets), is fully realized.

Hart of Dixie, particularly in this second season, has become one of my favorite hours of the week, and while it may not be revolutionizing the television landscape, that’s worth something.

5. Parks and Recreation (NBC)

Parks and Recreation has done something impressive–it’s hit its fifth season without breaking stride. Most shows, at about this point, start to broaden. While Parks and Rec does occasionally wobble on the tightrope between character and caricature (usually when Eagleton is involved), it’s mostly kept its footing by refusing to fear change.

Parks was smart–it solidified its relationships early on, built them to be unbreakable, so that the show could be a workplace comedy that did not have to remain in the workplace. Sure these people all met through the Pawnee Parks department, and many of them do still work there, in some capacity, but they aren’t tied to their office. Leslie can venture into the wider world of government, Tom can set off on his own business venture again, with a little more wisdom and guidance this time, the characters can learn and grow and stretch their wings and they’ll still have a reason to spend time with each other. These aren’t people who are trapped together, waiting out their time in some office purgatory, they’re friends.

And Parks and Rec proved that repeatedly last spring with the campaign arc. It brought its characters together in a new venue, only tangentially related to the titular workplace, and told a story that resonated emotionally, without sacrificing comedy (the scene where most of the cast tries to make their way across an ice rink to a looped Gloria Estefan clip is simultaneously one of the sweetest and funniest scenes they put out in the fourth season). Season 5, meanwhile, has taken on long-distance relationships, new jobs, several storylines about various characters’ attempts to find themselves, and perhaps the best proposal I’ve ever seen on television.

6. Girls (HBO)

In my worst moments, as my worst self, I am Hannah Horvath, and her continued existence as a television character is immensely comforting.

Girls also offered up one of the most honest and authentic fights between two characters that I have ever seen on television when Hannah and Marnie “broke up.” It would have made this list just for that.

7. Mad Men (AMC)

There were times this season when Mad Men got a little too English-major-y even for me, and I’m a former English major, but the way Matthew Weiner and company built the tension across the fifth season to the point where some act of violence was inevitable was beautiful to watch, as was Roger Sterling’s discovery of LSD, Peggy’s resignation from Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce, Sally’s quest for independence in go-go boots, and Ginsberg’s overconfidence. There were some misfires along the way–I love that Joan’s a partner, I hate the contrivance that got her there–but overall, the fifth season was a tour-de-force of storytelling.

8. Parenthood (NBC)

I’m not sure that there’s a better ensemble on television than the one that makes up Parenthood. Even when the story hits snags, as it has at various points along the way, the cast is so strong that they’ve managed to overcome anything that’s been thrown at them. Lauren Graham, Peter Krause and Mae Whitman have always been the acting powerhouses, but this season Monica Potter has shone especially bright in a cancer storyline that has mostly avoided the trite clichés (though it has still made me cry on an almost weekly basis), and Ray Romano has joined the cast to do what Ray Romano does, and well. I can already see the angry blog posts six months from now when the cast is overlooked by the Academy once again.

9. Community (NBC)

Much of the second half of Community’s third season, the half we awaited so anxiously during the unexpected mid-season hiatus that kept it off the air for a mere six months last winter (it’s now entering its eighth month in the much longer wait for season four), is a kind of hazy blur. There was a Law and Order episode, the study group got expelled from Greendale, Abed and Troy went to war with each other in a Ken Burns documentary…the details have gone fuzzy around the edges. But it’s a good sort of hazy blur, the kind you think back on fondly. I miss Community so much because I love Community so much, and I’m eagerly awaiting its return.

10. The Vampire Diaries (The CW)

The Vampire Diaries did something really gutsy at the end of its third season: it killed off the main character. Of course, Elena’s death doesn’t mean the end of Elena as a character–this show is about vampires, after all–but that didn’t make her loss any less sad. In its first three seasons, Vampire Diaries did enough to establish its characters and its mythology that when Elena woke up on a coroner’s slab in the season premiere you knew she wasn’t going to be quite the same person, and you knew she was on a path that she never wanted.

The fourth season of Vampire Diaries hasn’t been as strong as the first three were. Elena lost a lot of her agency in the transition, and when the season arc was introduced as a possible cure for vampirism it was hard not to roll my eyes. But the way the show packs in plot has always been impressive, and that’s still true. Vampire Diaries turned a questionable arc on its head in the second season–the strongest season to date–and there’s no reason to believe they won’t be able to do that again. And while not every episode this season has been a winner, a couple have been outstanding. “Memorial,” early on, gave the characters a chance to breathe for the first time in awhile, and offered an incredibly moving tribute to the loved ones that have been lost over the years, and the final episode of 2012, “O Come, All Ye Faithful,” had one of the show’s most elegant…slaughters. If they can maintain the quality of that episode, there’s no reason to believe they won’t have an outstanding 2013.